Writers

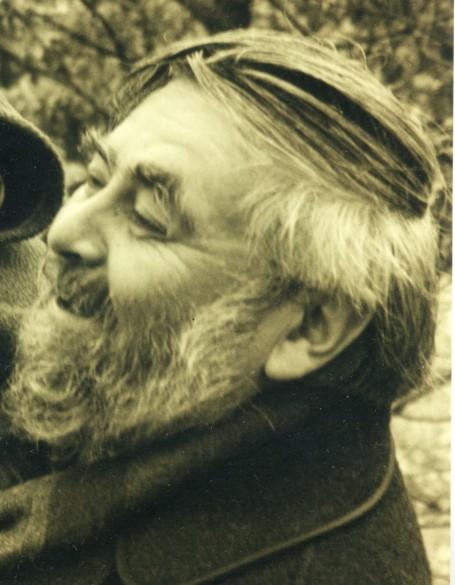

John Rety

John was born Réthy János in December 1930 in Budapest to a theatrical family. His mother Ilona Shaffer had been a performer and his father Istvan and uncle György were running the Hungarian Theatre Agency founded by his grandfather in 1882. Two of his uncles were literary journalists, his great-aunt was an opera singer and great-uncle an eminent mathematician. As a little boy he was sent to an English language nursery school and thus learnt only English nursery rhymes.

The family’s names had been buffeted by regulatory changes over the past half century – from Rothbaum to Réthy. In 1942 John’s grandfather Lipot was taken to court by an aristocrat because only Hungarian aristocrats should be allowed to have an ‘H’ and ‘Y’ in their names. So the family was left H-less and Y-less and John Réti arrived in London with his name mangled, anglicised and reversed.

The Réthys were Jewish enough to be persecuted by fascists but culturally or religiously Judaism did not have much of a presence in Jánci’s childhood. During the war John’s mother had him confirmed as a Catholic in the hope that it would provide some form of safety. John would say he was allergic to religion. John’s maternal grandfather disappeared during a pogrom in Serbia, from which his grandmother escaped by swimming the river Drava with her two little children on her back.

Many of John’s poems refer to the Second World War. These touch lightly, delicately sometimes as if a word or two of fact were as much as was possible to write of the reality. One must realise that they do describe very literally the awful impact on his childhood of the war and the siege of Budapest. The family was separated: mother, father, grandmother, János all hiding in different places – cellars, lofts, bathhouses, and János being the one who went between them carrying news. There were corpses in the streets, in the swimming pool. János’s father and uncles were put in internment camps. He visited his father and talked to him through the fence, thinking to persuade him to climb out while the guards were watching football, his father’s refusal and fear to do this had a profound impact on János. His beloved uncles disappeared, – Uncle Lajos who gave him a fountain pen and encouraged him to be a writer. John never spoke of the transportations but they are referred to in the lines “(the new jews)/ On the last train to Dachau”.

John’s most terrible experience in the war was the death of his maternal grandmother who had been his main carer before the family was split up. 38,000 civilians had been killed in the six weeks of the Siege of Budapest and yet the core of his family had survived. The day “peace” was declared his grandmother spoke out of concern to a very young Hungarian soldier. She advised him to take off his fascist armband since the Soviet troops were taking over. He shot her in the head. When John was told he ran weeping through the streets.

John was a pacifist. War was an impossible solution to anything. When he was sixteen he wrote a play about the war and how the adults had ruined the world for children. He got his friends to perform it on the steps of the Parliament building. His father had received veiled threats from the Communist authorities when he went for permission to reopen the Hungarian Theatrical Agency. Perhaps because of the play or perhaps because he saw that it would not be easy for János under communism, his father, in 1947, used his theatrical connections with the British Council to obtain a very rare travel permit to Britain, sponsored by the Labour MP John Parker.

Days before his seventeenth birthday John left Hungary on the Alberg Express for a winter holiday with his aunt in England,. Without realising it he had become a stateless person. Again and again through his poems there is the refrain of displacement. His aunt burned his passport and there was no way back.

John had thought he would be going home to University in Budapest. He declined his aunt’s plan that he should study at Pitman’s Secretarial College, London. Nevertheless he later taught himself enough to translate Latin and Greek in poems and read Anglo-Saxon and Hebrew poetry and the roots of English Literature. A Roman said of the people of Pannonia (later Hungary) that they were stultus or thick. Ulysses, The Romany Rye and Tristram Shandy were the books that John always returned to.

All games enchanted John. He learnt chess as a child and played in competitions throughout his life. ‘Why Two?’ was written on the return journey from playing for the British Seniors team in Austria. Through these poems there is the Lewis Carrollian delight in language games and plays on words. The nonsense, wisdom, satire, mathematics and language of Carroll were very dear to John.

At seventeen he became apprenticed to a Czech publisher, Mr Prager of Lincolns Prager and learned the craft from him. He then plunged into Soho bohemia and published young writers in his little magazines The Cheshire Cat, Intimate Review, The Fortnightly and wrote his novel of the bohemian experiences, Supersozzled Nights in 1951. The poem ‘Declaration’ hints at the discomfort of being a foreigner on the English literary scene.

In the 1960s John was an editor of the anarchist paper Freedom for several years there is something of this in the poem ‘Freedom’. He also was deeply involved in the political squatting movement of the late ’60s and early ’70s. Resistance to the powerful property magnate Joe Levy in Camden Town ended in his own family’s eviction and loss of home and livelihood.

In the 1970s John went to the City and Guilds Art School and became a painter. Some years later nearly all his paintings were stolen. He didn’t paint again. Some images he tried to recover in sketch books. Maybe some became poems, certainly there is film making and performance art in his poetry.

In 1982 John and his partner Susan and myself, their daughter, were given the keys of a building in Torriano Avenue owned by Camden Council. It became a temporary home, and then Torriano Meeting House evolved out of their common interests. They played host to the writers of the ’50s once again – John Heath-Stubbs, Stephen Spender, Bernard Kops. And host to striking miners’ wives, cabaret performers, antiwar groups, musicians, playwrights, artists; host to dreamers and utopians of the Stonehenge Campaign. John began to publish poetry again under the imprint Hearing Eye, poets from the old days and new people that came through the door. In this collection there are memories of some of these – Arthur Jacobs, poet and Hebrew scholar whose work John perhaps respected above all others; Harriet (Bee) Cutler, a playwright, who ran the Lantern Theatre, a sister venture to Torriano Meeting House in many ways; Madge Herron in ‘Some Poets Are Even Worse’; John Gravelle, teacher and talker who reads his newspaper throughout ‘In the Museum’.

John was stateless until 2007, when he was obliged by international changes to choose a state, Hungary or Britain, because it became impossible to travel abroad without a national passport. They said that it was no longer permissible to be stateless. The Hungarians wouldn’t have him because he couldn’t prove he was a Hungarian. He evaded the Britishness test but in the end acquiesced to swear allegiance to the Queen because, he said, she, like himself had experienced war in her youth. He was surprised to find that an insecurity about belonging that he had never realised was there, lifted. After the ceremony he said that he was born again in Eastbourne.

From the afterword by Emily Johns to ‘Notebook in Hand’

John Rety reading ‘In the Museum’

Reviews

John Rety

£3